Developing the Budget

In This Section

In general, Washington state’s budget process cannot be characterized by any single budget decision model. Elements of program, target and traditional line-item budgeting associated with objects of expenditure (e.g., salaries, equipment) are all used, along with a performance budgeting approach in decision making.

In 2017, meeting the state’s constitutional duty to fully fund K-12 education was an enormous challenge and the top budget priority. Agencies were directed to limit their requests for new funding and to focus on the highest priority services that deliver significant performance improvements and outcomes for the people of Washington.

During the pandemic era, Washington experienced plummeting revenue collections and agencies were directed to reduce spending for FY2021 and re-base maintenance level budgets for state programs not protected from reductions by state constitutional provisions or federal law for their 2021-23 biennial budget requests.

Eventually, revenue collections rebounded and in developing the 2023-25 biennial budget, OFM used Results Washington goals, outcome measures and action plans — along with agency strategic plans and performance measures — to prioritize spending within and across agency budgets. Improving efficiency and streamlining the operations of state government is an expectation the Governor has of all agencies.

Development of the 2025-27 biennial budget brought new challenges, with slowing revenue collections and accelerating costs due to inflation and other factors, leaving Washington with a large budget gap to close. Ultimately, this was accomplished through a combination of targeted budget cuts and efficiencies, along with increased taxes.

State government is organized among 125 agencies, boards and commissions representing a wide range of services. While many state agencies report directly to the Governor, others are managed by statewide elected officials or independent boards appointed by the Governor. Most agencies receive their expenditure authority from legislative appropriations that impose a legal limit on operating and capital expenditures. Appropriations are authorized for a single account, although individual agencies frequently receive appropriations from more than one account.

A few agencies are “nonappropriated,” meaning that they operate from an account that is legally exempt from appropriation. Expenditures by these agencies are usually monitored through a biennial allotment plan. There is no dollar limit as long as expenditures remain within available revenues and are consistent with the statutory purpose of the agency.

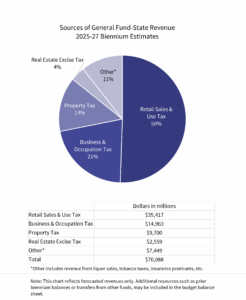

The state’s budget and accounting system includes 804 discrete accounts, which operate much like individual bank accounts with specific sources of revenue. The largest single account is the General Fund-State (GF-S) account. State collections of retail sales, business, property, and other taxes are deposited in this account. Expenditures from the GF-S can be made for any authorized state activity, subject to legislative appropriation limits.

Other accounts are less flexible. Certain revenues (for example, the motor vehicle fuel tax or hunting license fees) are deposited in accounts that can be spent only for the purpose established in state law. In budget terms, these are referred to as “dedicated accounts.”

Washington receives most of its revenue from taxes, licenses, permits and fees, and federal grants. Each individual revenue source is designated by law for deposit in specific accounts to support state operating or capital expenditures.

The chart below displays the major revenue sources for GF-S expenditures in the current biennium. The Department of Revenue collects most of these revenues.